Analyzing Our Model's Behavior

Which parameters have the greatest impact?

Our model has many parameters. Some of them are well-grounded in empirical data, but others are more uncertain and require "judgmental forecasting" (or, "guessing") to estimate. In this section, we investigate how sensitive key model outcomes are to different parameters.

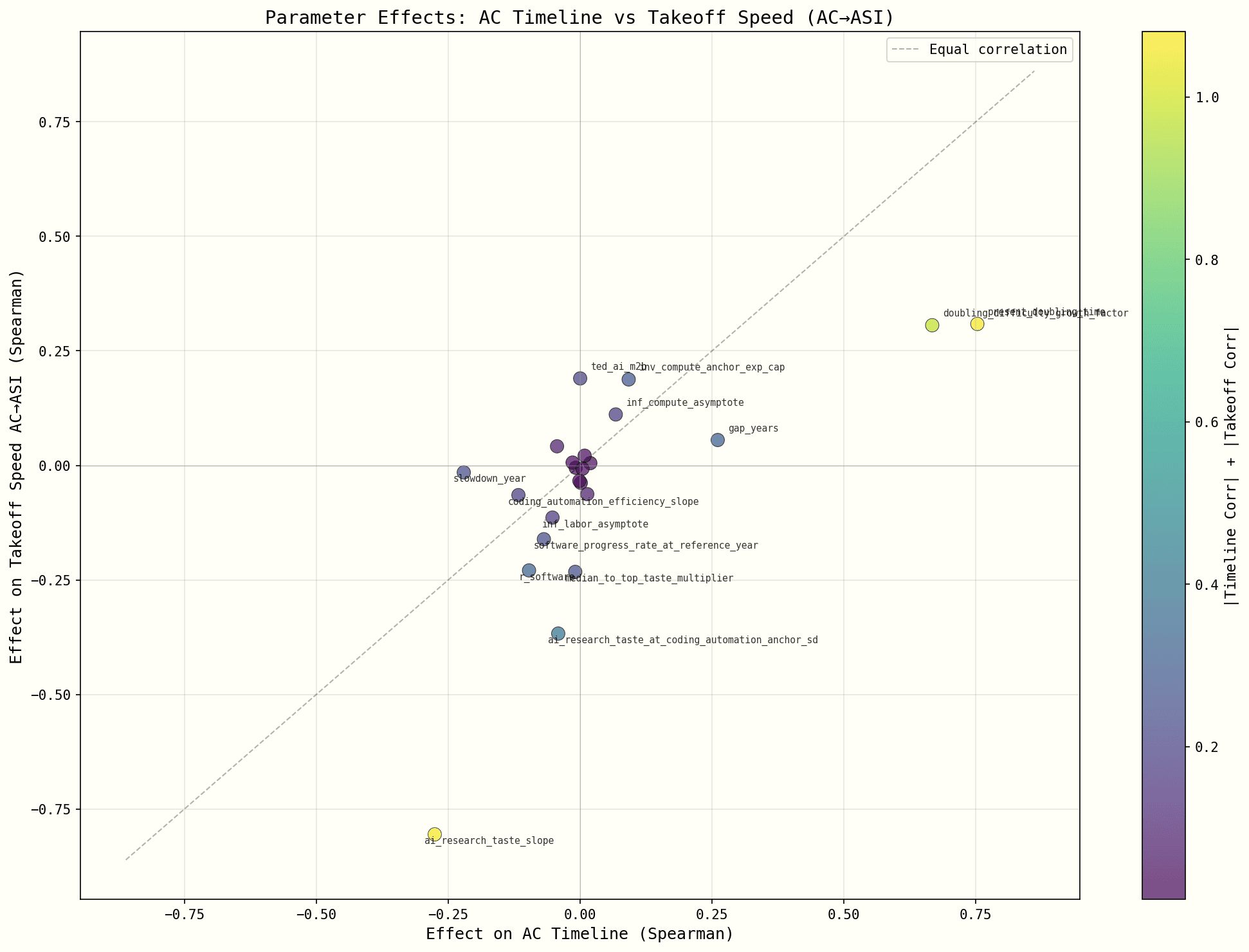

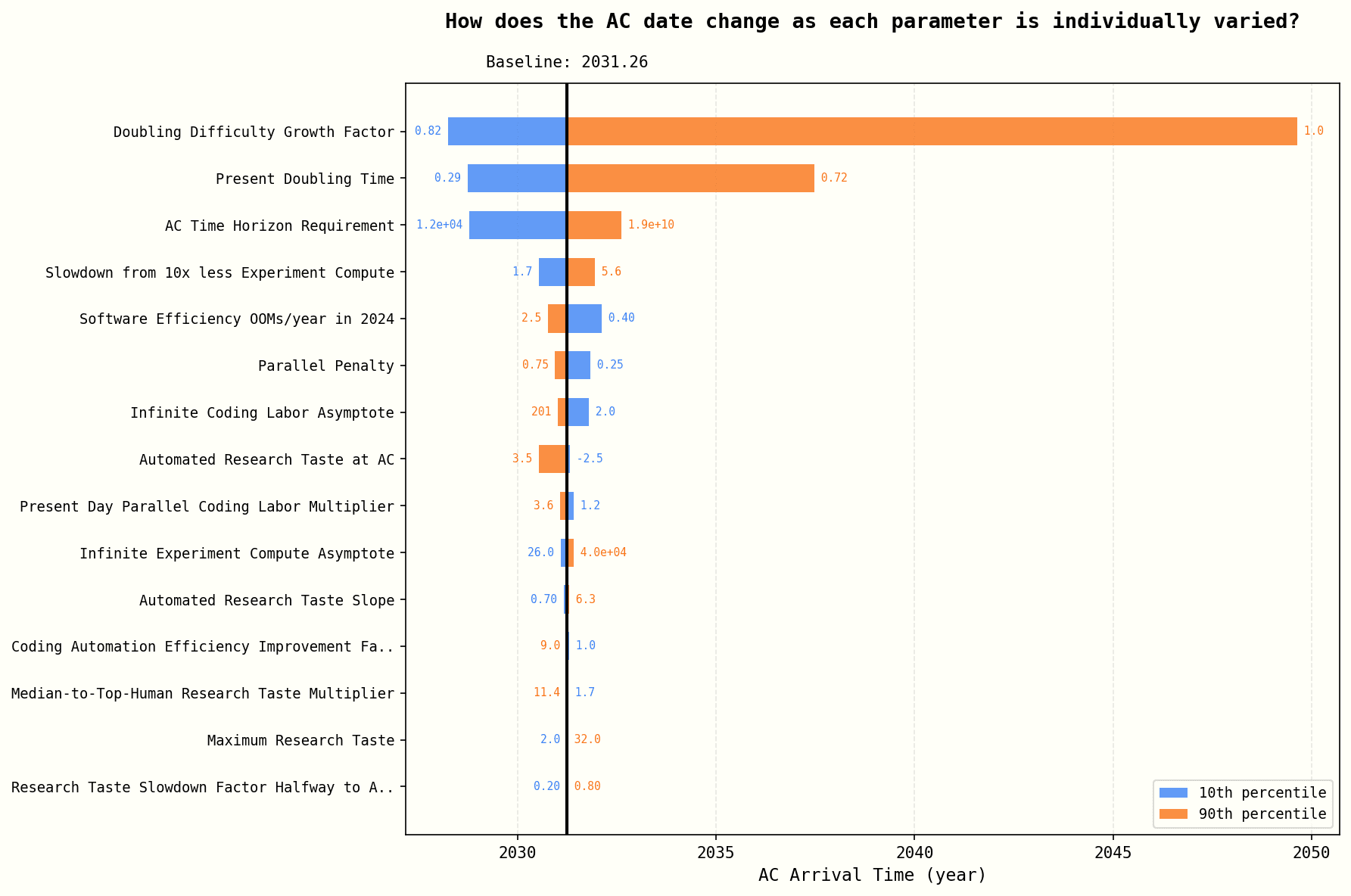

One-at-a-Time Sensitivity: Timelines to AC and Takeoff from AC to ASI

Beginning with all parameters set to our median estimates of their values, we individually change each one to our 10th percentile estimate and our 90th percentile estimate, then plot how the timeline and takeoff speed changes. The size of the "spread" resulting from these changes gives a simple measure of how much of our uncertainty in the outcome comes from our uncertainty about each parameter.

The most important parameters affecting the time to AC are:

- Doubling difficulty growth factor;

- Present doubling time for time horizon;

- Time horizon requirement for AC.

The first two parameters together determine the mapping from log(effective compute) to the AI's time horizon. The doubling difficulty parameter controls how steeply super or sub-exponential this mapping is, and the present doubling time gives the initial growth rate of time horizon. It's intuitive that these would be important: they tell us how difficult it is to double time horizon in the present and how that difficulty will change in the future. In particular, even a small change in the doubling difficulty growth factor d can make a big difference since we take powers of d to find doubling times after many doublings.

It's also intuitive that the AC time horizon requirement should have a significant effect: if you need a time horizon of 100 work years to automate all coding, that's going to take longer than if you need a time horizon of 6 months.

The other parameters shown in the graph influence how gains in effective compute are converted into AI software R&D uplift. The sensitivity analysis reveals these are less important for AC timelines than the three parameters discussed above. This makes sense: before getting to AC, coding bottlenecks on the tasks the AIs can't complete yet. And the AIs' research taste is not yet good enough to make a big difference in selecting good experiments.

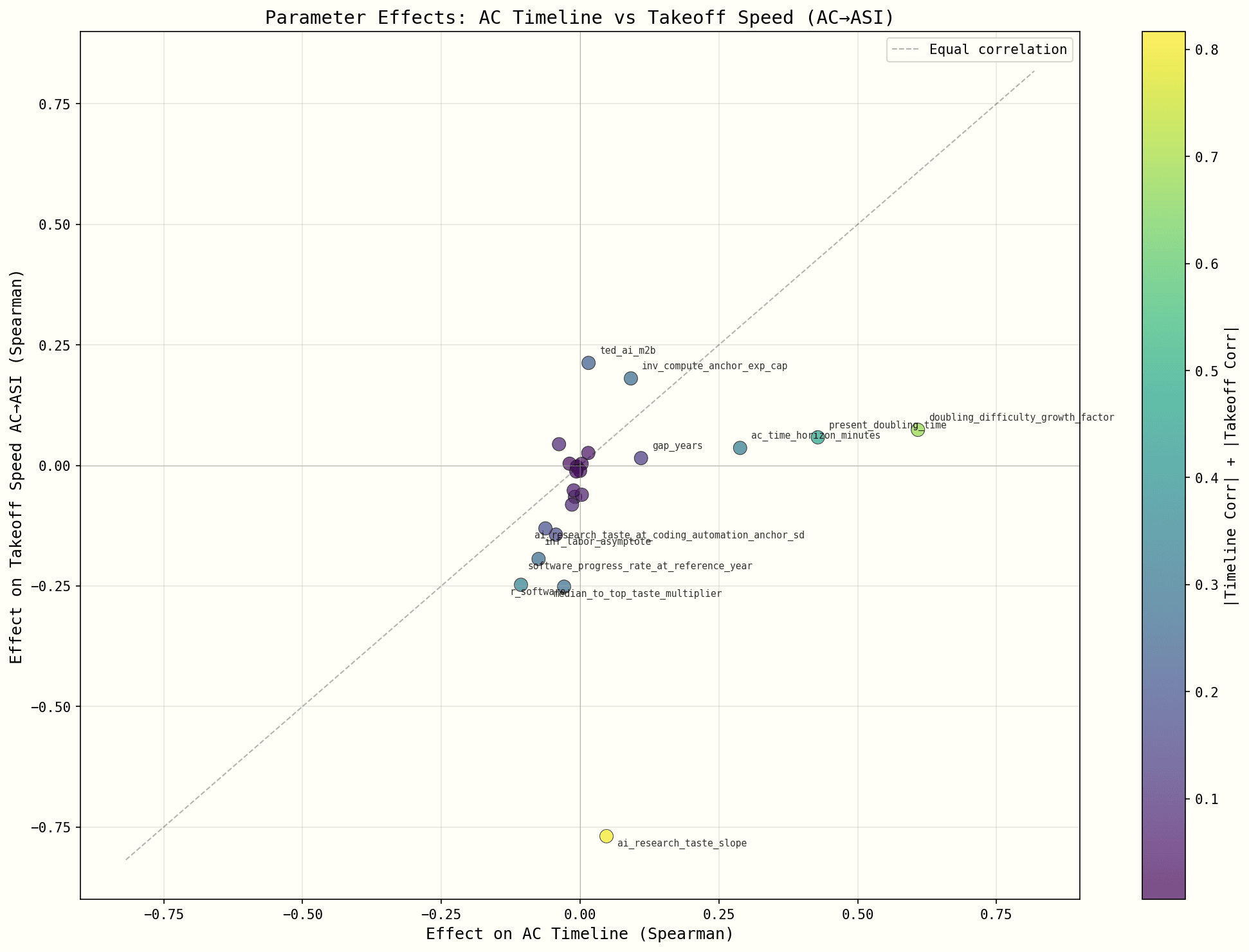

Now let's look at what parameters takeoff speeds are most sensitive to.

The most important parameters are:

- The ones determining how quickly AIs' research taste improves as effective compute increases: automated research taste slope and the median-to-top research taste multiplier. We call how quickly AIs' research taste improves as effective compute increases m when discussing software intelligence explosions. m is primarily a function of these 2 parameters.

- The software efficiency growth rate in 2024, which influences the rate at which (experiment) ideas become harder to find. Along with the m described above this parameter has lots of influence on the extent to which there is a software intelligence explosion: see here for discussion.

- Median-to-top-human jumps above SAR needed to reach TED-AI: This determines at what research taste capabilities ASI is achieved, very directly affecting the time taken from AC to ASI.

- Those controlling the level of compute bottlenecking in experiment throughput (infinite coding labor asymptote and slowdown from 10x less experiment compute). The most important parameters, i.e. the ones above, have to do with research taste rather than coding because coding gets bottlenecked on experimental compute. That said, coding automation still matters for takeoff: we see that parameters controlling the experiment throughput CES have a significant impact, particularly ones controlling the level of compute bottlenecking.

Correlation Between Timelines and Takeoff

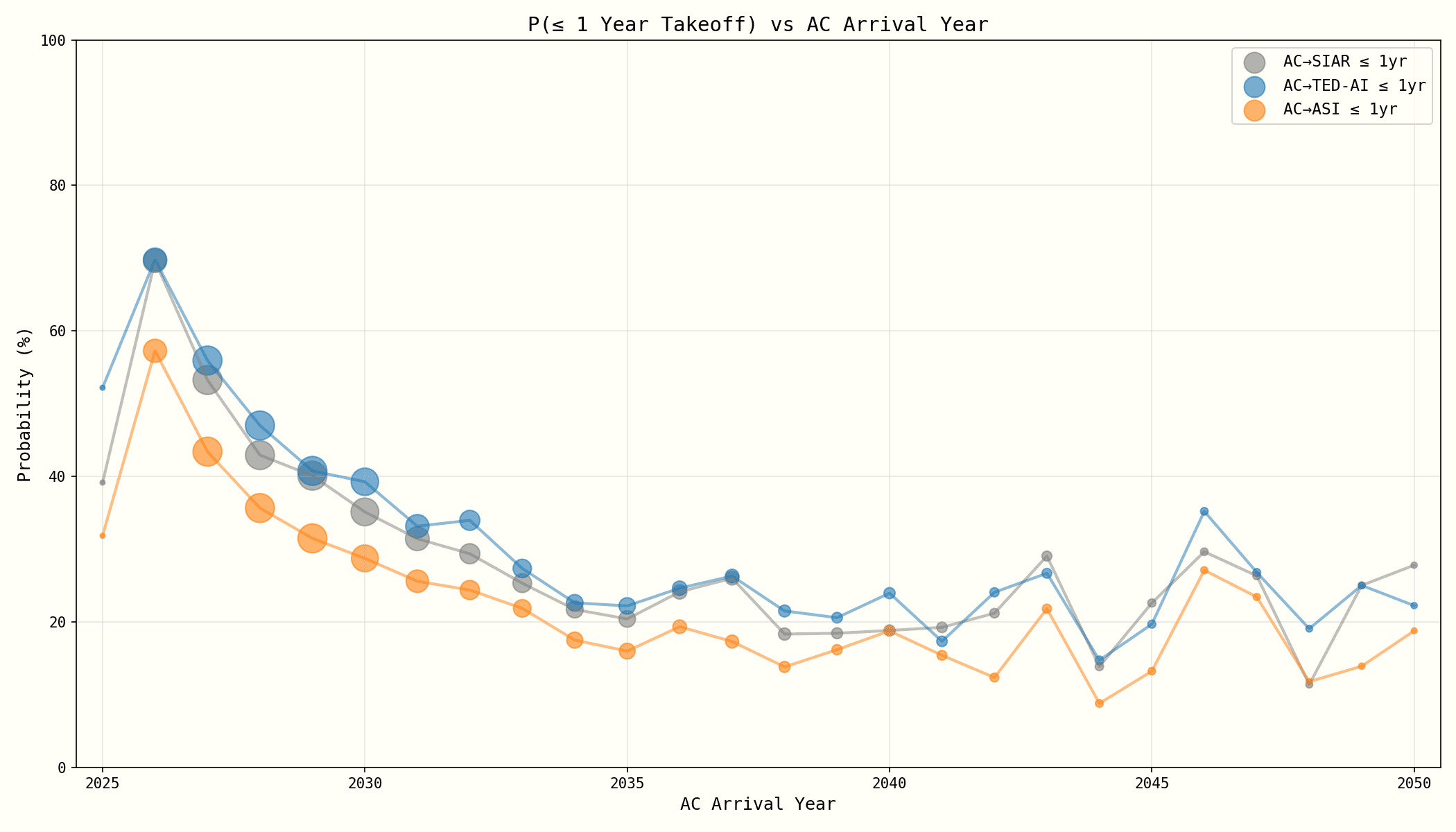

We observe that shorter timelines to the Automated Coder milestone (AC) are correlated with faster takeoffs. This plot shows how the empirical probability of "fast" takeoff (meaning less than 1 year) varies conditional on different AC arrival years.

For example, the probability of a one-year AC-to-ASI transition is 42% if AC comes in 2027, but only 16% if AC comes in 2035. Why are shorter timelines to AC correlated with faster takeoffs?

There are two potential sources driving this pattern. For one, our Monte Carlo simulation draws correlated samples for some of the parameters.

Input Parameter Correlations

The correlation matrix below shows the correlations between sampled parameters in our Monte Carlo simulation. These correlations are specified in the sampling configuration to capture dependencies between parameters.

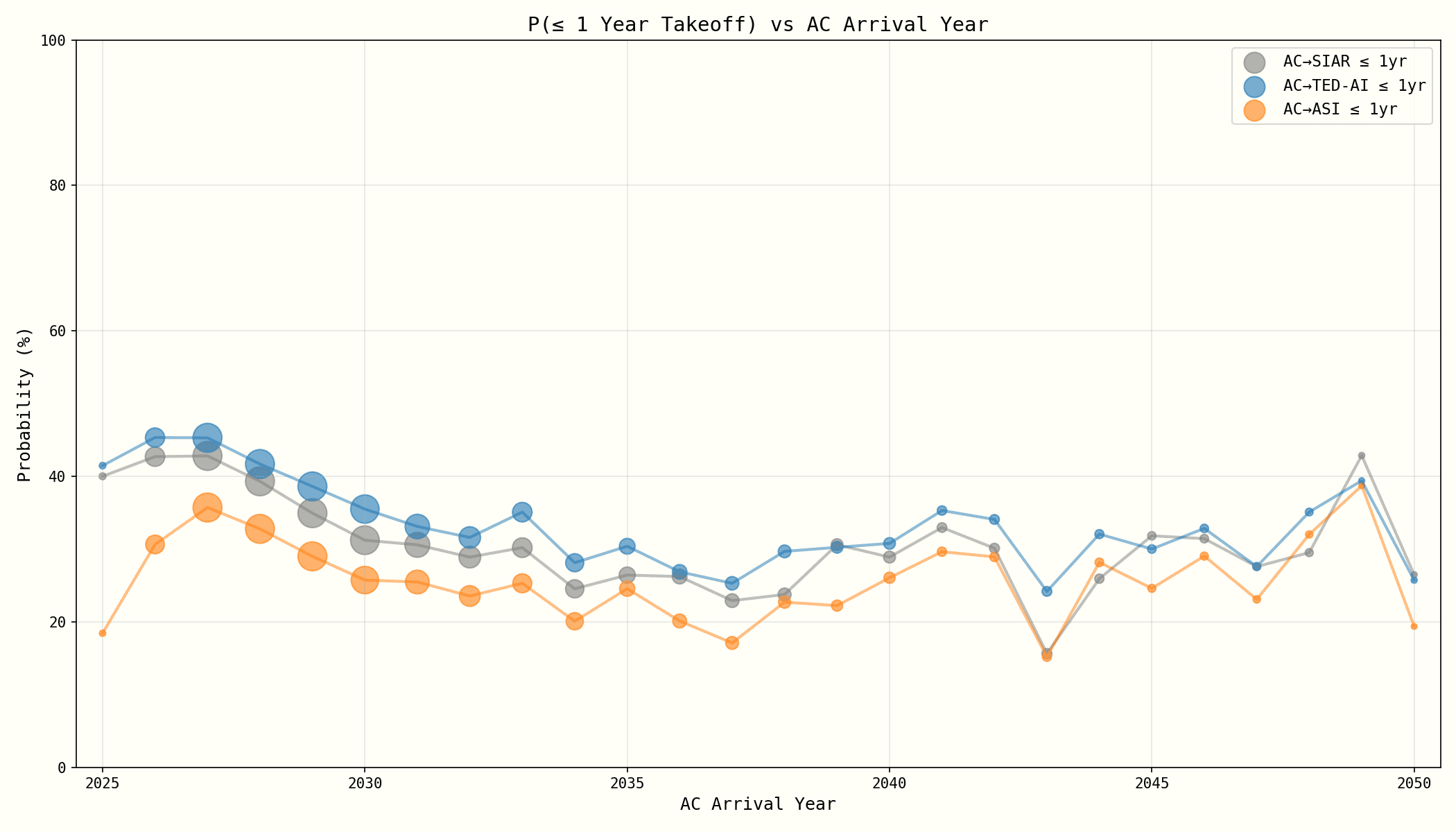

The other potential driver would come from the intrinsic model dynamics. To isolate this source, we plot the probability of 1-year takeoff with various AC arrival years, but with no correlations between parameter values:

We see that the correlation is still significant, but lower than when we included correlations between parameter values. It appears that the change mostly derives from the shorter-timeline scenarios.

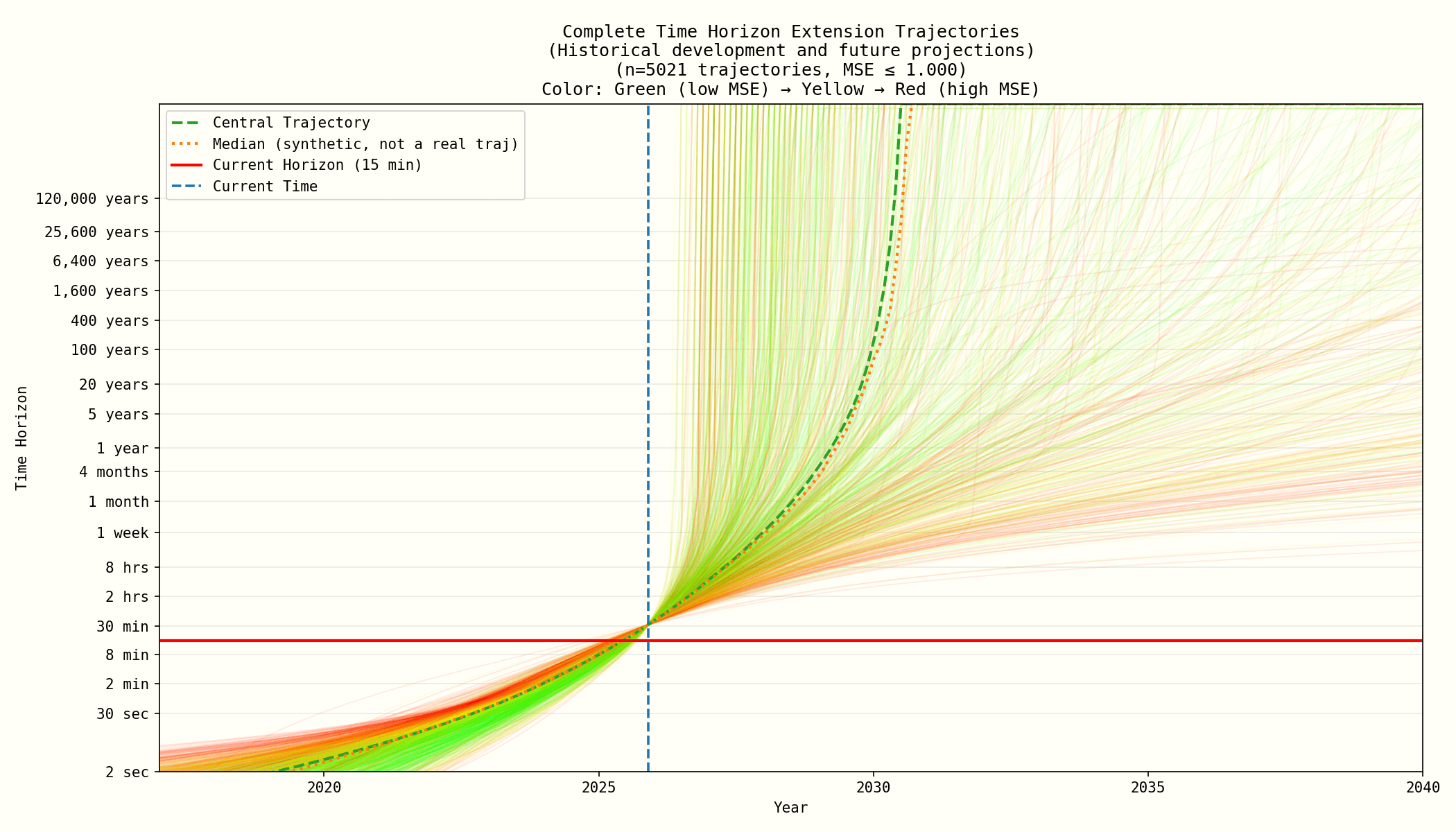

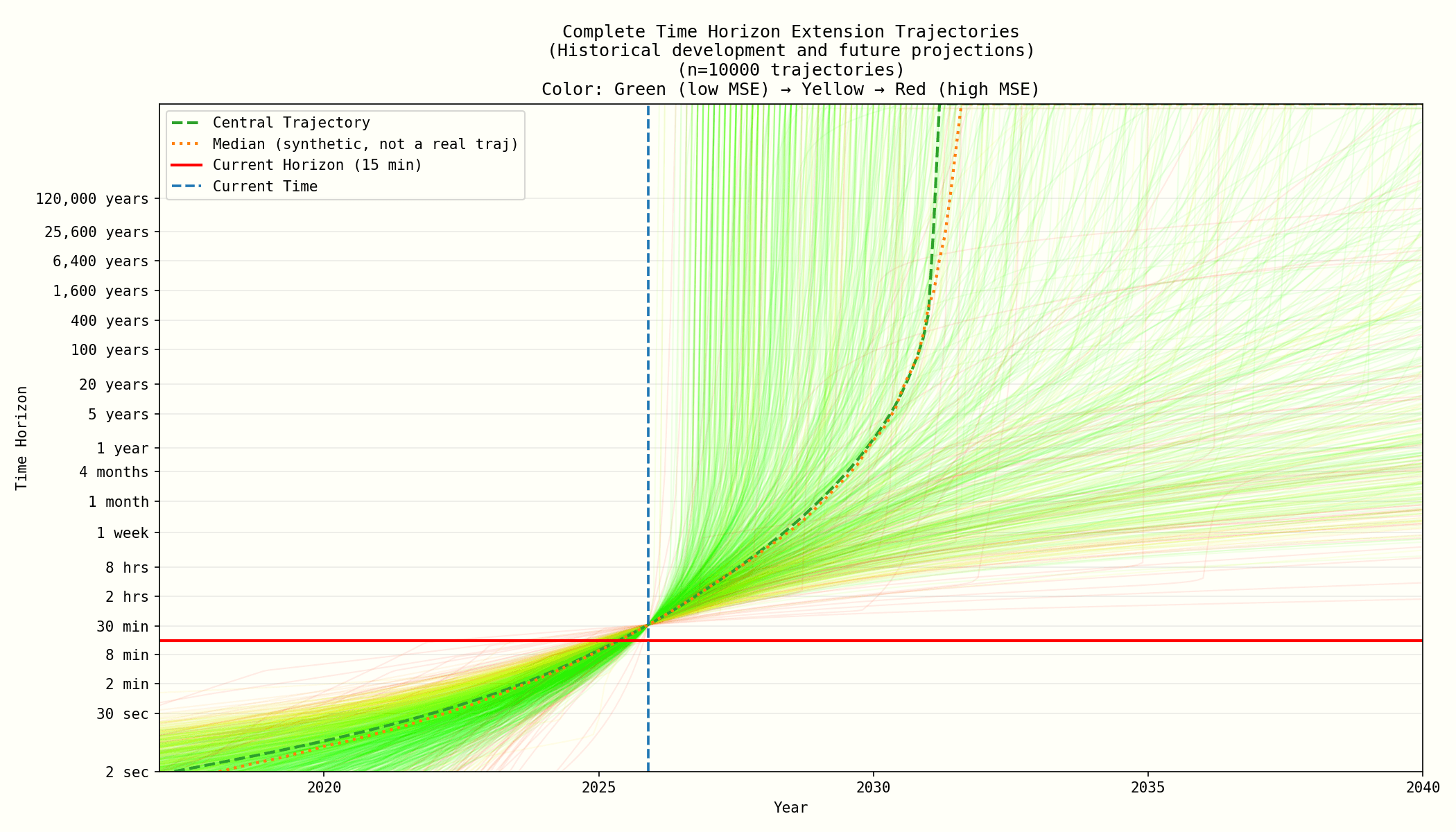

Time Horizon Trajectories

Here are all the time horizon trajectories, shaded by how well they backcast the METR points according to mean squared error (MSE). We view this sort of backcasting as an important exercise but not the end-all be-all, given that the data we have are so limited. Thanks to titotal's review of our previous model for prompting us to do more of this.

Filtered Trajectories (MSE ≤ 1.0)

Here are approximately the top 1/3 of trajectories in terms of how well they backcast. Trajectories that backcast better tend to reach higher time horizons earlier.