The AI Futures Model

We've significantly upgraded our timelines and takeoff model! We’ve found it useful for clarifying and informing our thinking, and we hope others do too. We plan to continue thinking about these topics, and update our models and forecasts accordingly.

Why do timelines and takeoff modeling?

The future is very hard to predict. We don't think this model, or any other model, should be trusted completely. The model takes into account what we think are the most important dynamics and factors, but it doesn't take into account everything. Also, only some of the parameter values in the model are grounded in empirical data; the rest are intuitive guesses. If you disagree with our guesses, you can change them above.

Nevertheless, we think that modeling work is important. Our overall view is the result of weighing many considerations, factors, arguments, etc.; a model is a way to do this transparently and explicitly, as opposed to implicitly and all in our head. By reading about our model, you can come to understand why we have the views we do, what arguments and trends seem most important to us, etc.

The future is uncertain, but we shouldn’t just wait for it to arrive. If we try to predict what will happen, if we pay attention to the trends and extrapolate them, if we build models of the underlying dynamics, then we'll have a better sense of what is likely, and we'll be less unprepared for what happens. We’ll also be able to better incorporate future empirical data into our forecasts.

In fact, the improvements we’ve made to this model as compared to our timelines model at the time of AI 2027 (Apr 2025), have resulted in a roughly 2-4 year shift in our median for full coding automation. The plurality of this has come from improving our modeling of AI R&D automation, but other factors such as revising parameter estimates have also contributed. These modeling improvements have resulted in a larger change in our views than the new empirical evidence that we’ve observed. You can read more about the shift in our blog post.

Why our approach to modeling? Comparing to other approaches

In our blog post, we give a brief survey of other methods for forecasting AI timelines and takeoff speeds, including other formal models such as FTM and GATE but also simpler methods like revenue extrapolation and intuition: you can read that here.

What predictions does the model make?

You can find our forecasts here. These are based on simulating the model lots of times, with each simulation resampling from our parameter distributions. We also display our overall views after adjusting for out-of-model considerations.

With Eli's parameter estimates, the model gives a median of late 2030 for full automation of coding (which we refer to as the Automated Coder milestone or AC), with 19% probability by the end of 2027. With Daniel’s parameter estimates, the median for AC is late 2029.

In our results analysis, we investigate which parameters have the greatest impact on the model’s behavior. We also discuss the correlation between shorter timelines and faster takeoff speeds.

Our blog post discusses how these predictions compare to the predictions of our previous model from AI 2027.

Limitations and all-things-considered views

In terms of how how much they affect Eli’s all-things-considered views (i.e. Eli’s overall forecast of what will happen, taking into account factors outside of the model), the top known limitations are:

Not explicitly modeling data as an input to AI progress. Our model implicitly assumes now that any data progress is proportional to algorithmic progress. But data in practice could be either more or less bottlenecking. Along with accounting for unknown unknowns, this limitation pushes Eli’s median timelines back by 2 years.

Not modeling automation of hardware R&D, hardware production, and general economic automation. We aren’t modeling these, and while they have longer lead times than software R&D, a year might be enough for them to make a substantial difference. This limitation makes Eli place more probability on fast takeoffs from AC to ASI than the model does, especially increasing the probability of <3 year takeoffs (from ~43% to ~60%).

Meanwhile, Daniel increases his uncertainty somewhat in both directions in an attempt to account for model limitations and unknown unknowns and makes his takeoff somewhat faster for reasons similar to Eli’s.

A more thorough discussion of this model’s limitations can be found here, and discussion of how they affect our all-things-considered views is here.

High-level description of the model behavior

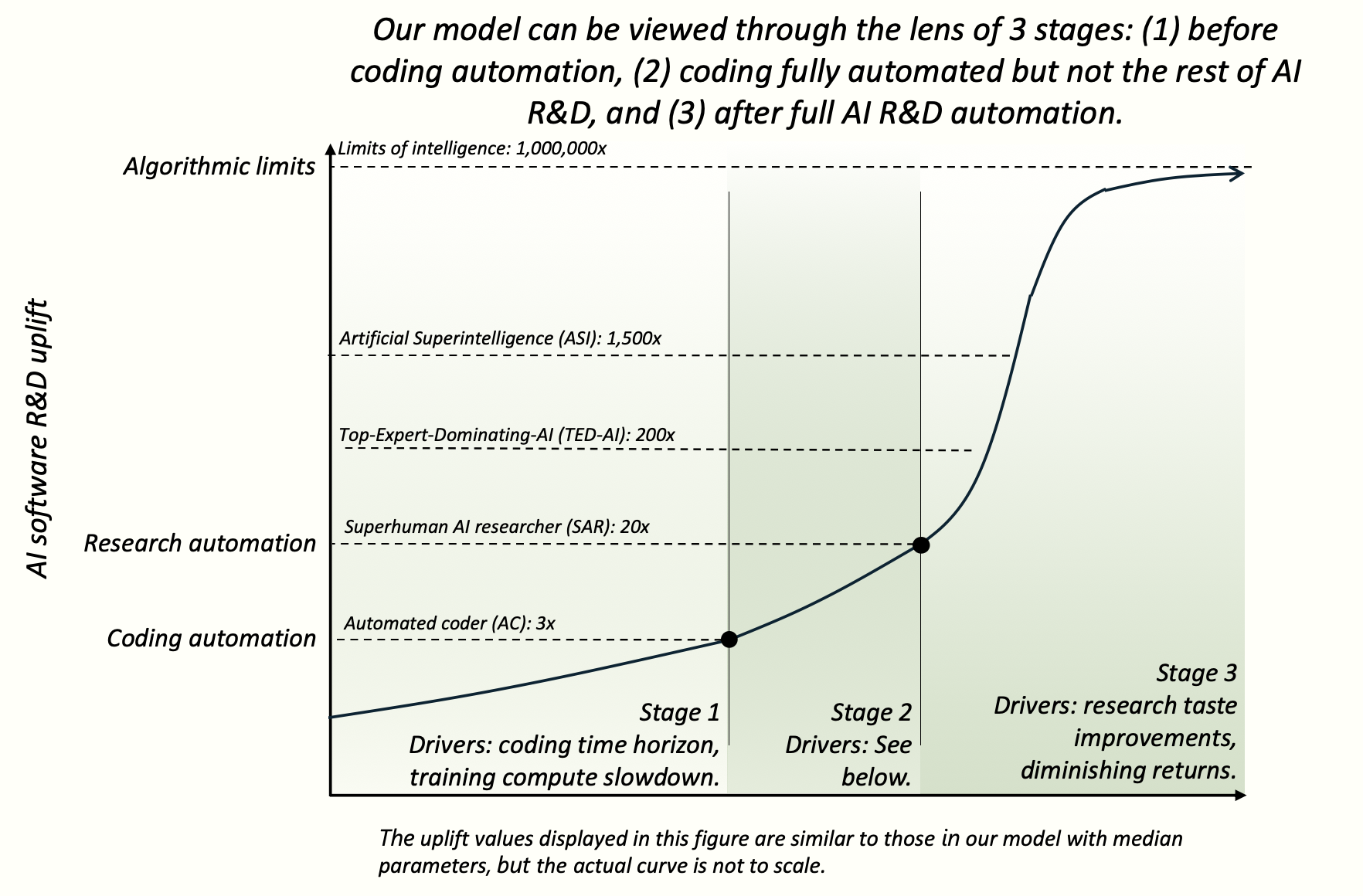

We start with a high-level description of how our model can intuitively be divided into 3 stages. The next section contains the actual explanation of the model, and accompanies the arrowed diagram on the right.

Our model's primary output is the trajectory of AIs' abilities to automate and accelerate AI software R&D. But although the same formulas are used in Stages 1, 2, and 3, new dynamics emerge at certain milestones (Automated Coder, Superhuman AI Researcher), and so these milestones delineate natural stages.

Stage 1: Automating coding

Stage 1 predicts when coding in the AGI project will be fully automated. This stage centrally involves extrapolating the METR-HRS coding time horizon study.

Milestone endpoint: Automated Coder (AC). An AC can fully automate an AGI project's coding work, replacing the project’s entire software engineering staff.

The main drivers in Stage 1 are:

- Coding time horizon progression. We model how the coding time horizon trend progresses via parameters for (a) the effective compute increase currently required to double time horizon, (b) how this doubling requirement changes over time (i.e. whether time horizon growth is superexponential in log(effective compute)), and (c) the time horizon required for AC. In some simulations, we include a “gap” on top of reaching the time horizon requirement, in case doing well on the METR dataset doesn't immediately translate to doing well on real-world coding tasks.

- Partial automation of coding speeding up progress.

- Training compute growth slowing. We project that training compute growth will slow over time, due to limits on investment and the speed of building new fabs. This has a big impact in ~2035+ timelines.

Stage 2: Automating research taste

Besides coding, we track one other type of skill that is needed to automate AI software R&D: research taste. While automating coding makes an AI project faster at implementing experiments, automating research taste makes the project better at setting research directions, selecting experiments, and learning from experiments.

Stage 2 predicts how quickly we will go from an Automated Coder (AC) to a Superhuman AI researcher (SAR), an AI with research taste matching the top human researcher.

Milestone endpoint: Superhuman AI Researcher (SAR): A SAR can fully automate AI R&D.

The main drivers of how quickly Stage 2 goes is:

- How much automating coding speeds up AI R&D. This depends on a few factors, for example how severely the project gets bottlenecked on experiment compute.

- How good AIs' research taste is at the time AC is created. If AIs are better at research taste relative to coding, Stage 2 goes more quickly.

- How quickly AIs' research taste improves. For each 10x of effective compute, how much more value does one get per experiment?

Stage 3: The intelligence explosion

Finally we model how quickly AIs are able to self-improve once AI R&D is fully automated and humans are obsolete. The endpoint of Stage 3 is asymptoting at the limits of intelligence.

The primary milestones we track in Stage 3 are:

- Superintelligent AI Researcher (SIAR). The gap between a SIAR and the top AGI project human researcher is 2x greater than the gap between the top AGI project human researcher and the median researcher.

- Top-human-Expert-Dominating AI (TED-AI). A TED-AI is at least as good as top human experts at virtually all cognitive tasks. (Note that the translation in our model from AI R&D capabilities to general capabilities is very rough.)

- Artificial Superintelligence (ASI). The gap between an ASI and the best humans is 2x greater than the gap between the best humans and the median professional, at virtually all cognitive tasks.

In our simulations, we see a wide variety of outcomes ranging from a weeks-long takeoff from SAR to ASI, to a fizzling out of the intelligence explosion requiring further increases in compute to get to ASI.

To achieve a fast takeoff, there usually needs to be a feedback loop such that each successive doubling of AI capabilities takes less time than the last. In the fastest takeoffs, this is usually possible via a taste-only singularity, i.e. the doublings would get faster solely from improvements in research taste (and not increases in compute or improvements in coding). Whether a taste-only singularity occurs depends on which of the following dominates:

- The rate at which (experiment) ideas become harder to find. Specifically, how much new “research effort” is needed to achieve a given increase in AI capabilities.

- How quickly AIs' research taste improves. For a given amount of inputs to AI progress, how much more value does one get per experiment?

Continued improvements in coding automation matter less and less, as the project gets bottlenecked by their limited supply of experiment compute.